|

| Photo © Prof. Charles R. Magel |

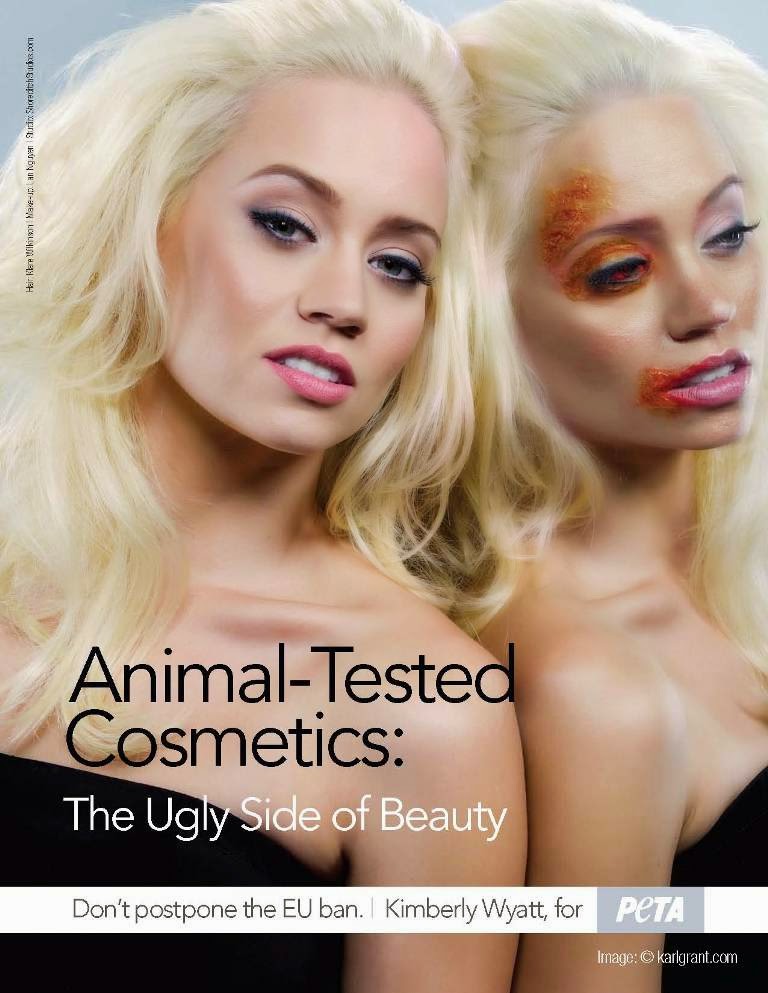

Culture Jamming Cover Girl

By

Geraldine Lemonde and Morgan Woodward

Many arguments for and against animal experimenting may be put in place. It is true that this type of testing helped in the development of medicines and vaccines within the scientific and medicinal research area. Although, the following comes into play: is it really necessary that animal testing be used within the cosmetics industry? It is important not to forget that this type of industry is totally unnecessary in the development of human beings. Therefore, could we say that it is killing millions of animals per year for the sake of popular culture? To be more precise, it is 219 animals that are killed per minute in the United States due to animal testing (Kondrashova, 2013). A large part of this incredible number of animals is due to the cosmetics industry. Many might ask why alternative methods for testing are not utilized; the answer is because it is cheaper to test on animals and use animal rendering as it will “minimize the cost of production and maximize profits” (Kondrashova, 2013, p.2).

|

| Photo © Elephant Journal |

Types of Animal Testing

|

| Rabbits Undergoing Draize and Skin Toxicity Testing. Photo © HubPages.com |

The “mouse local lymph node assay” is a test where a “substance is applied to the dorsum of the ears of mice for three consecutive days” (Adler & al., 2011, p.400) and the regression is observed. These are only few of the many different types of testing on animals. It is to be noted that animals eat, inhale or absorb the tested substances (Topulus, n.d.). Other areas of animal testing include phototoxicity, acute toxicity, genotoxocity, mutagenicity, toxicokinetics, melabolism, photosensitization, carcinogenicity, and more (Adler & al., 2011). The amount of chemicals that animals are exposed to in the laboratory as well as the ways they are exposed to them is simply not humane.

Animal Rendering

|

| Euthanized Animals in Rendering Plant Photo © Dogs Naturally |

Animal rendering is far from being the only way cosmetic industries pollute the environment. So many chemicals and toxins are released in the environment each year; 5, 705, 670, 380 pounds to be precise. (Donahue, 2009) Despite this, there is still confusion about global warming. Cosmetic producers are particularly the biggest users of palm oil, a vegetable oil that can be found in Indonesia and Malaysia. In order to extract this oil, thousands of tropical trees must be destroyed. Procter & Gamble, the owner of Cover Girl, “purchases palm oil from suppliers that are actively engaged in burning forests and draining peat lands in Indonesia” (Sahota, 2014, p. 8), thus encouraging the destruction of the environment. Also, in 2012 research found diverse chemical toxins that stem from cosmetics in Minnesota waterways, polluting not only that single waterway, but also the ones related to it. (Sahota, 2014) It is clear that this is not the only waterway that is contaminated by cosmetic chemicals, seeing that there are industries around the world and the waste has no choice but to be released into water basins.

Toxic Chemicals You May Not Be Aware Of

Not only are the industrial chemicals released in the environment, but a toxin, which is defined by “a substance that by chemical action can kill of injure a living thing [and] creates an irritation of harmful effect in the body” (Donahue, 2009, p.14), is easily absorbed by the skin when cosmetic products are applied to it. There are on average 2 983 chemicals in a cosmetic product; 884 of which are toxic, 314 of which can cause “biological mutation”, 218 of which can cause “reproductive complications”, 778 of which can cause “acute toxicity”, 146 of which can cause tumors and 376 of which can cause “skin and eye irritation.” (Donahue, 2009) The toxins found in cosmetics include but are not limited to Nitrate-Nitrire, PEG Stearates, PEG-80 Sorbitan Laurate, Phenoxethanol, Polyethylene Glycol, Toluene, Acetone, Butylate, Hydroxytuloene, Benzonic Acid, Carbon Monoxide, Kaolin, Lead, and many more. Thus, this “handy” toxin allows mascara flexibility, the softening of the skin and the deeper penetration of lotions into the skin. What the clientele does not know, though, is that this toxin had extreme effects on male lab animals, such as “testicular atrophy, reduced sperm count, and defects in the structure of the penis.” These defects are potential contributors to human health effects, as much to males and females (especially pregnant women). The Procter & Gamble company has been proven to hold the biggest amount of Phtalates in their products, including Cover Girl.

Adding to the problem is that there are many biases within regulations of toxic release of chemicals in the environment. The particular chemical I previously mentioned, Phtalate, is “considered a hazardous waste and are regulated as polluants in air and water [whereas they] are essentially unregulated in food and cosmetics.” This means that cosmetic companies are allowed to put any amount of Phthalate in their products, but not in the environment. Additionally, the consumer who is trying to purchase Phthalate-free products might be biased with the labeling since “a typical shopper will not know that “dybutil phthalate” is the same thing as “butyl ester” or even possibly “plasticizer.” Additionally, there are some industries trying to “green-up.” Sahota (2014) explains how Eco-Labels are “voluntary schemes” that “attempt to communicate certain aspects of sustainability to consumers... The irony of this fact is that “there are no national or regional regulations for natural and organic cosmetics.” (p. 217 - 218); in other words, there are no standards for Eco-Labels. The same goes with animal testing; there are no laws against animal testing in the United-States and in Canada. So, if a label reads, “this company does not do animal testing that is required by the law,” it is essentially a bias for the consumer into thinking that the product is “friendly” (Topulos, n.d.). Altogether, the unclear and unspecific laws about chemical consumption and the biases found on product labeling are extremely misleading.

In conclusion, the cosmetics industry, Procter & Gamble and Cover Girl particularly, is using its resources in a way that is not safe for animals and the environment. The unethical issue of animal testing, where animals are raised to be tortured to death and are continued to be used after, is shocking and repulsive. The same goes for polluting the environment as well as filling their cosmetic products with harmful chemicals. These companies lie to their customers in order to sell more. They say that one day, the cosmetics industry will be honest and equitable. Considering the factors discussed the real question is will it ever happen?

References

Adler, S., Basketter, D., Creton, S., Pelkonen, O., van Benthem, J., Zuang, V., Coecke, S. (2011). Alternative (non-animal) methods for cosmetics testing: current status and future prospects-2010. Archives of toxicology, 85(5), 367-485. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0693-2

Environmental Working Group. (n.d.). Beauty Secrets. Mindfully.org.

Donahue, R. (2009). The pollution inside you: What is your body dying to say? USA: Safe Goods

Haugen, D. M. (2007). Animal experimentation: Opposing viewpoints. Detroit: Thomson/Gale

Kondrasova, A. (2013). Death for beauty. WordPress.com.

Sahota, A. (2014). Sustainability: how the cosmetics industry is greening up. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

Sun, S. (2012). The truth behind animal testing. Young scientist’s journal, 12, 83-85. doi: 10.4103/0974-6102.105076

Topulos, S. (n.d.). Animal Testing Research and Cruelty Free Shopping Guide. Milton.edu.

About The Author

Morgan Woodward is presently studying at Champlain College Lennoxville located in Quebec, Canada. Mysteries Behind Beauty was written as part of an assignment for Consumerism, Leisure and Popular Culture in the Department of Humanities.

Call For Submissions!

Would you like to be a Guest Contributor? The Wicked Academic is always looking for quality contributions to both the website and the academic online journal. For further information check out The Printing Press and FAQ section.